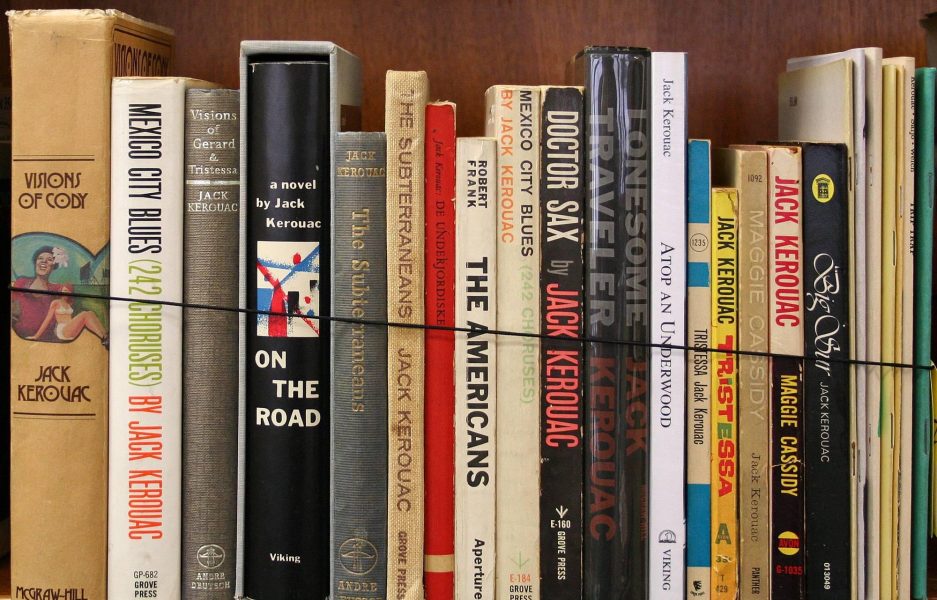

At the website for the Henry Miller Memorial Library, they mistakenly state as fact that Miller “didn’t like the Beats.” Contrarily, readers of Kerouac will recognize as fact that Miller, in 1959, wrote a three page introduction for Kerouac’s novel, The Subterraneans. What is cloudy is how Miller came to write the introduction, Kerouac’s feelings for Miller as a writer and did he really get so drunk at San Francisco’s Vesuvio’s in the Summer of 1960 that he “missed an important meeting” with Miller as claimed by local legend? My guess for the latter, is that such sordid legends help sell more drinks like “The Jack Kerouac” (rum, tequila, and orange juice ) to wanna-beat bohemian tourists, but there is a grain of truth to the whole affair that is worth writing about [as it was in 2008 by this worthy blog.]

On January 16, 1956, Kerouac more or less dismissed Miller in a letter to Philip Whalen, rebuking Whalen not to waste his time reading (among others) “that special idiot, what’s his name, Miller, or Hemingway […]”Despite this careless toss-off, Miller had made no secret of his open admiration for Kerouac’s then-new novel, The Dharma Bums (1958) after he was mailed a review copy from Viking Press to his Big Sur home. Miller, impressed by Kerouac’s book wrote Pat Covici, senior editor at Viking, that “from the moment I began reading the book I was intoxicated.” Miller also wrote, as reprinted in Charter’s second volume of Kerouac’s selected letters (p. 157): “No man can write with that delicious freedom and abandonment who has not practiced severe discipline …. Kerouac could and probably will exert tremendous influence upon our contemporary writers young and old … we’re had all kinds of bums heretofore but never a Dharma bum, like this Kerouac”.

Miller’s enthusiasm didn’t wane when he sent his review copy to Lawrence Durrell who was no fan of Beat writing. Miller expressed: ““I say it’s good, very good, surpassingly good. The writing especially. He’s a poet. His prose is poetry. Or, shall I say, the kind of poetry I can recognize.” Durrell responded: “God knows Kerouac may yet turn into a writer. He’s young and hard working. But what a devastating picture of what young intellectuals are saying and doing over there; they need a week at a French lycée to think and construct.”

News of Miller’s reception reached Kerouac living at Northport, Long Island. He wrote Allen Ginsberg on October 15, 1958 that this positive reception was a “real breakthrough for us” (as it may have been for Ginsberg, who wrote Kerouac about a year earlier that Miller had attended the obscenity trial for “Howl and other Poems”).

Miller reached out to Kerouac, mailing him letters, according to Kerouac, “every week.” One such letter reads as follows:

Big Sur 12/9-58

Dear Jack Kerouac – I don’t know where Ginsberg gets his mail, so you write him a postcard, will you, and thank him for his letter. Tell him that the review he wrote of your D.B. in the Village Voice (N.Y.) struck me as quite, quite wonderful . . .I felt, when I read D.B. that you must have written millions of words before- and I see, via A.G., that you have. Salute! P.S. Do you read French? I know, or hear, that you are French Canadian, but–? Anyway, if you do, I’d like to send you “Salut Pur Pelville” by Jean Giono.”

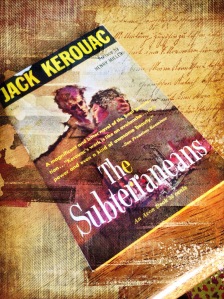

Sufficiently bowled over, Miller agreed to write a preface for Kerouac’s forthcoming novel, relegated to the equivalent of a pulp paperback with a lurid painting of the lead character, Leo Percepied resembling Kerouac, and a white woman (despite her being African American in the novel) in place for Mardou Fox. Miller writes within the novel’s first three pages:

“When someone asks, “Where does he get that stuff?” say: “From you!” Man, he lay awake all night listening with eyes and ears. A night of a thousand years. Heard it in the womb, heard it in the cradle, heard it in school, heard it on the floor of life’s stock exchange where dreams are traded for gold. And man, he’s sick of hearing it. He wants to move on. He wants to blow. But will you let him?”

Though the rights for the novel were sold to MGM, America most definitely would not “let him blow.” On the Road’s popularity began to wane as the Fifties slipped into the 1960s and Kerouac was regarded as passe. Kerouac, all too aware that his short-lived career was on the downward slope, accelerated his drinking.

Poet and publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti, alarmed at Kerouac’s rapid alcoholic intake, offered him free use of his new cabin at Big Sur (where Miller was living at the time). Back home, the Kerouacs (Jack and his mother, Gabrielle) were suffering the outrageous slings of the American press bent on demistifying and demolishing Kerouac’s literary reputation. When a cartoon appeared in Newsday of a smiling beatnik, replete with a cup of coffee, goatee beard and bongos, standing under the headline “Ike Visit Cancelled,” the cartoonist also placed next to him a “book by Jack Kerouac.” Incensed, Gabe got drunk and penned a letter to Newsday stating that she and her son were Republicans, “we like Ike” and that Newsday were “bums and liars.” They were both drinking, hard, so that when Long Island drinking companion John Kokell came by Kerouac’s house (also drunk), Jack called his mother “ugly” in front of her. Kokell attempted to borrow $3000 from Kerouac, to which he was turned away. He drank harder until he couldn’t breath anymore. When an encyclopedea salesman came to his door to have him sign for $300 in books that he forgot he ordered, he signed “GO FUCK YOURSELF” on the signature line. When he read somewhere that Norman Mailer called him “dishonest,” he revealed in his diary that his hands began to shake with “dismay.” At home he had no privacy. Requests came in the mail, people wanting things, constantly. It was, in his assessment, the “shit American Suburban horror” that he always wanted to avoid, but now found himself inextricably enmeshed with his aging mother. He worried about witches, paranoid that they were “whispering” in his ear via the radio or television. He wondered about the phallic television antennas popping up on every house in Northport. Television, he accurately detected, was the new plague. He was incredulous that scores of Americans would go on vacation, drive “hundreds of miles” just to watch TV in someone else’s house.

On the morning of July 1, 1960, he woke up seized by stomach cramps that had him just about writhing on the floor. He suspected a bleeding ulcer, but instead he was beset by diarrhea of “black poison.” When companion Charley Byers and his cousin rang Jack’s doorbell, they offered to take him out for a drink, Kerouac desisted, explaining that he was sick with shot nerves. He knew all too well his need to escape, and so he left the “gooky city” that was beginning to scare him. He said to himself in his diary, “One fast move or I’m gone.” But there would be no escape from the demons whirling in his head like dervishes: “I just cant take all this sea of sinister human hate engulfing my head— I simply must go away from NY awhile + be calm awhile in my own thoughs.”

Though he wanted to leave on July 20th, Kerouac was dissuaded by the threat of a railroad strike. Instead he left earlier on July 15 after a series of “fights” escalated the tension of family drama in his house, after being visited by his sister and nephew. So, off to San Francisco he went, finding himself in an ever-spiraling circle of Dantean proportions. Ferlinghetti arranged a dinner with Kerouac and Miller. However, Kerouac was in the throes of an exhausting bar crawl. The meeting with Miller and Kerouac’s ensuing guilt was explained in Kerouac’s novel, Big Sur (1962):

“(already feeling awful guilt about Henry Miller anyway, we’ve made an appointment with him about a week ago and instead of showing up at his friend’s house in Santa Cruz at seven we’re all drunk at ten calling long distance and poor Henry just said “Well I’m sorry I dont get to meet you Jack but I’m an old man and at ten o’clock it’s time for me to go to bed you’d never make it here till after midnight now”) (his voice on the phone just like on his records, nasal, Brooklyn, goodguy voice, and him disappointed in a way because he’s gone to the trouble of writing a preface to one of my books) (tho I suddenly now think in my remorseful paranoias “Ah the hell with it he was only getting in the act like all these guys write prefaces so you dont even get to read the author first”) (as an example of how really psychotically suspicious and loco I was getting).”

When it was time for him to leave for the cabin, he walked to the bus station, cashed his check and bought a bus ticket to Monterey (and Kerouac made note in his diary that the “nice” bus clerk recognized him by calling him “Jack”). He walked to Chinatown and ate his first meal in two days before returning via Skid Row to buy a bag of groceries. In his Skid Row room, Kerouac packed his belongings and left, sleeping on the bus all the way to Monterey. By two in the morning he could smell the bay. He hired a cab to Bixby Canyon and, after being dropped off he hiked, scared, the rest of the way in complete darkness, tromping through the high cathedral-like shadows of the mountains.

The rest, as they say, is history.

[Note: Henry Miller never got to meet Jack Kerouac.]